Crete (6 page)

Samaria is the most famous of the Cretan gorgesâhence the crowds. The numerous others are generally deserted and differ widely in character and constitution. Those who know them have their favorites, rather as is the case with Aegean islands or Roman fountains. For Rackham and Moody, the one best loved is the gorge of Therisso, a ten-mile drive from Chania into the northern fringes of the White Mountains, with its lush vegetation, its shaded, meandering course, and its walls like hanging gardens decked in a variety of endemic plants. For those with a taste for the bare and elemental, there is the gorge that lies behind the Kapsas Monastery in the coastal desert strip on the far southeast of the island, where the average annual rainfall is something like four hundred millimeters. (Compare this with an estimated two thousand millimeters at the highest points in the White Mountains to gain an idea of the range of rainfall from west to east, astonishing on such a small island.) This is a stark and arid landscape, one that the ascetic prophets of old might have felt at home in.

My own favorite is the gorge entered near the village of Zaros in the province of Iraklion. It offers a combination of effects which I think of as essentially Cretan. A little to the west of the village a signed track leads up to the monastery of Agios Nikolaos, a distance of about a mileâon foot from the village it's much less. The entrance to the gorge is higher up, so you can rest in the tranquil, shaded courtyard of the monastery or view the fourteenth-century paintings in the church before setting off for the walk. A climb of half an hour by a steep path brings you to the hermitage of St. Euthymios, a cave with a tiny church built into it and two fine wall paintings still surviving. So you have a monastery, a cave hermitage, and a splendid walk. The gorge of Zaros is short by Cretan standards, perhaps two miles in length, with a good, well-defined path and marvelous views of the Psiloritis mountains continuously before you as you go. This is one of those times on the islandâand they are manyâwhen the print of humanity blends in harmony with the unspoiled wildness of the landscape to make an impression quite unforgettable.

However, Crete is rich in alternatives, and if the walk seems too strenuous or the weather too hot, a drive of a few miles west from Zaros, toward Kamares, brings you to another monastery, that of Vrondisi, one of the most beautiful on the island and one of the most important in the history of Cretan monasticism, a center of education and religious art in the period of creative vitality and renewal that took place in the final decades of the Venetian occupation.

The monastery is dedicated to St. Anthony, patron saint of hermits. The outer courtyard, before the main gates, is full of the sound of water falling from the mouths of lion heads sculpted in relief on the fountain, and a plane tree with the dimensions of a cathedral arches over the whole area. It was at Vrondisi that Damaskinos, one of the most important of Cretan religious painters, did some of his best work. Six of the icons he painted here are on permanent display in the gallery of the church of Agia Ekaterini in Iraklion.

On the day of our visit, one of the two remaining monks was sitting in the shade of the fig tree at the entrance, talking gravely to local people. He greeted us with a kind of dignified courtesy. There was no attempt to ask questions or sell us anything, no obtrusive presence making sure that we obeyed the prohibition about taking photographs inside the church, where the rows of frescoed apostles and the Christ of the Last Supper in the apse presented the same grave dignity as they regarded us in the dimness.

Coming back to gorges, that of Samaria has the distinction, together with some smaller ravines that run parallel to it, of giving access, at its southern end, to the sea. So having completed the long, hot walk, emerging at Agia Roumeli, you are presented with the prospect not only of a cold drink but also a refreshing plunge.

This, however, presents you also with a choice as to which first. To reach the shore you have first to pass the bars. We had been distinctly thirsty for quite some time, having foolishly neglected to bring anything to drink with us. Also, the idea of simply sitting down for a while was one that had considerable appeal. The struggle was of the briefest. The bar won hands down. I don't think cold beer has ever tasted so good. By the time we had each had a liter of it, all desire for a refreshing plunge had left us. It was all we could do to make the walk to the boat.

The boats from here go in either direction along the coast. Generally, people take the one going westward to Souyia, thence returning to Chania by road. But going the other way, to Chora Sfakion, and using it as a base, one can see the mountain villages on the southern side of the White Mountains, the region known as Sfakia.

This is a wild and remote region where roads are few, the climate unrelenting, and the living conditions harsh. The atmosphere of abandonment and desolation one sometimes feels here is in a sense the price the people have paid for their indomitable spirit, their refusal to accept a foreign yoke. This has meant that their villages have been devastated again and again. Through all the centuries of occupation the Sfakians were never completely subdued, resisting Venetian and Turk and German from their mountain fastnesses, and, when for the moment these invaders did not threaten, turning on their own neighbors with equal ferocity. To give one example among many, the people of Zourva were attacked from the rear by the Sfakians in the revolution of 1866, thus saving the Turks from defeatâan attack due entirely to resentment against their fellow countrymen for assuming the leadership of the revolution, a privilege which the Sfakians regarded as exclusively their own. If ever scientists succeed in identifying a warrior gene, it will certainly be found in the people of Sfakia. Their lawless and rapacious spirit is illustrated in the local version of the Creation. This, as related by Adam Hopkins, begins with an account of the gifts bestowed by God on other parts of the island:

â¦olives to Ierapetra, Agios Vasilios and Selinou; wine to Malevisi and Kissamou; cherries to Mylopotamos and Amari. But when God got to Sfakia only rocks were left. So the Sfakiots appeared before Him armed to the teeth. “And us, Lord, how are we going to live on these rocks?” And the Almighty, looking at them with sympathy, replied in their own dialect (naturally): “Haven't you got a scrap of brains in your head? Don't you know that the lowlanders are cultivating all these riches for you?”

It is entirely appropriate that the most splendid of all Cretan heroic legends of resistance against the Turks in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries should center on the exploits of a Sfakian, Daskaloyiannis, who was born at Anopolis, a village in the foothills behind Chora Sfakion. Also appropriate, since the Sfakians are great singers and storytellers, that he should have found a chronicler from among them. Sixteen years after his death, his story was dictated in a thousand lines of epic verse by an illiterate bard named Pantzelios, a cheesemaker by trade. The scribe was a shepherd. He took down the story slowly and probably painfullyâit is hard to believe that he was much accustomed to writing. Here is his description of the process, as translated by Michael Llewellyn Smith who includes an account of the Daskaloyiannis Revolt in his excellent study of the island:

I began, and wrote a little every day.

I held the paper and I held the pen

And he told me the story and I wrote it bit by bit.

To this poem, despite mistakes and heroic exaggerations, we owe most of what is known about the celebrated revolt of Yannis Vlachos, otherwise known as Daskaloyiannis, “John the Teacher,” a title of respect rather than a literal description, as in fact he was a ship owner and one of the wealthiest man on the island. It is difficult to imagine anyone less like the Cretan rebel chieftain of tradition. He dressed generally in European clothes, spoke several languages, and had traveled widely in the Mediterranean region. And his political aims went far beyond the usual narrowly territorial uprisings of the Sfakians. He dreamed of freeing Crete and all Greece from the Ottoman occupation and returning her to the comity of Christian nations.

Naturally enough, he turned to the Russians, his co-religionists, for help, and they found in him a useful ally. In fact, from the Russian point of view his appearance was providential. The Russo-Turkish war had just broken out, and it was the job of Count Orloff, Catherine the Great's minister, to foment rebellion against the Turks wherever possible. He found in the enthusiastic and credulous Daskaloyiannis a perfect pawn.

The plans were laid. The Cretan uprising was to coincide with a revolt in the Peloponnese. Orloff undertook to support the rebels from the sea. Armed with this promise, Daskaloyiannis was able to carry the Cretans along with him. The flag of revolt was raised in March 1770. The Sfakian force, probably no more than a thousand men, marched on Chania, the idea being to keep the Turks bottled up inside the walls until the Russian fleet arrived. But the days passed, and no ships were sighted. Without the Russian guns the rebellion was doomed. By May the Turks had entered Sfakia with a force of twenty thousand troops. Heavily outnumbered, the rebels were compelled to retreat to their mountain fastnesses. Still no help came from the Russians.

The Sfakians fought with astonishing bravery and endurance, but by the following spring the situation was desperate, their last lines of defense had been crossed. At this point the pasha of Iraklion wrote to Daskaloyiannis inviting him to give himself up.

Trust my letter, whatever they may tell you,

And so leave Sfakia with men to live in her.

When you come and we talk together

All will be settled and we shall be friends.

With this letter another arrived, this one from Daskaloyiannis's brother, who had already fallen into Turkish hands. In it he urged Daskaloyiannis to accept the pasha's invitation. But he managed to insert into the letter a prearranged code signal indicating that his brother was to take no notice of either letter. In spite of this, Daskaloyiannis decided to surrender. He knew now, after his brother's warning, that he had small chance of saving his life, but he thought he might get better terms for his followers. He made his farewell to wife and children:

Come to my arms, children, for me to kiss you,

And be wise until I return again.

Listen to your mother and to your own peopleâ

You have my prayers.

He gave himself up and was taken to Iraklion. The pasha greeted him with every appearance of friendship, offered him food, wine, coffee, and tobacco, then began a polite interrogation. What was the cause of the revolt? Why didn't you bring your complaints to me?

The causeâyou are the cause, you lawless pashas.

That's why I decided to raise Crete in revolt,

to free her from the claws of the Turk.

Hardly the most conciliatory of replies. But then, he hadn't much hope of clemency. And when the pasha, still courteously, asked him for the names of the ring-leaders among the rebels of the Peloponnese, he proudly and angrily refused. You are wasting your breath, he said. Your net has a hole in it, do not hope to catch any fish. This defiance was the end of him. On the pasha's orders, he was taken to the main square of Iraklion and flayed alive. According to the poem he endured this frightful punishment without uttering a sound. But his brother, tied up and obliged to watch the hideous spectacle, could not endure the sight and lost his senses. According to the traditional version of the story, he died mad. The remnants of the Sfakian force, after some years of captivity, returned to the desolation of their ruined villages.

It is difficult to associate the Anopolis of today, the village of the hero's birth, with those desperate and sanguinary days. The thriving village rests quietly in its fertile upland plain, surrounded by fruit trees and fields of wheat. Sfakia as a whole has changed a great deal. The people speak the same language and wear the same style of dress as other Cretans. They are more prosperous now, generally speaking, and more peaceable. They are not always very communicative, but they don't carry weapons anymoreânot openly, at least. Communications are better, but the mountains on this part of the south coast plunge abruptly down into the sea, the coastal strip is extremely narrow, hardly more, in many places, than a rocky foreshore. From east to west there are no good roads, and often no roads at all. Those that run north to Chania skirt the White Mountains on either side; there is no way through the heart of the range. And one does not need to wander far from what few roads there are in Sfakia to encounter a landscape that in its bleakness and remoteness recalls the savage past.

Â

MUTABLE FORTRESS

Eastward along the coast from Chania, the main road keeps close to the shoreline of Souda Bay until it reaches Kalami, then veers south, turning away from the sea for a while, joining it again as one approaches Rethymnon. Near where this change of direction occurs, on a plateau overlooking the bay, a mile or two inland, lie the ruins of Aptera, once one of the strongest Greek city-states on the island. Of very ancient foundation, going back to at least 1000

B.C.

, its time of greatest splendor was during the Hellenistic period, from about 500

B.C.

onward. The city was severely damaged by earthquake early in the eighth century

A.D.,

and in 823 it was sacked and more or less completely destroyed by Arab invaders, an event from which it seems never to have recovered. Excavationâwhich still continues on the siteâhas uncovered the remains of massive stone walls, nearly three miles in length, enclosing a wide area, evidence of the importance the city once enjoyed.

After thirteen centuries the evidence of violent events is half buried, grassed over, softened out of recognition, whether it is the violence of natural forces or the savagery of human beings. We had the site to ourselves; in the two hours that we spent there we saw almost no one. We felt a great sense of peace, though we didn't talk about it until later, in this place of ancient battles and dead passions. Perhaps, in my case at least, a kind of acceptance or resignation: All the works of man will in the end be a wide plain, empty of all but stones and flowers, like this one.

Violence and the fear of it are still in evidence, however; it is the single unifying factor in the ruins of this once mighty and prosperous city that has seen so many tenants. All those who came here, having established their power, lived in fear of having that power taken from them and sought in one way or another to guard against attack. The remains of German machine-gun emplacements lie not far from a Turkish fortâor what is left of itâlooking out over Souda Bay, and over another fortress lower down with its cannon still in place, and, still lower, over the island fortresses which guard the approaches to this superb natural anchorage, surely one of the finest in the world. Below the German redoubts and the Turkish bastions, Greek naval vessels, guns mounted, pass to and fro.

The city itself was named to commemorate a kind of battleâor so the legend goes. Somewhere among the nearby mountains the Muses challenged the Sirens to a musical contest, and the Sirens lost. In their mortification they stripped off their wings and flung themselves down from the cliffs into the bay, where they were transformed into islands. Another case of Cretan myth stealing: The island of the Sirens, which Odysseus passed on his journey home to Ithaka, is held by everyone else to have been Anthemoessa, off the Italian coast. The Muses, left in the possession of the field, decked themselves in the feathers to celebrate their victory. The literal translation of “Aptera” is “Wingless” or “Featherless,” and there was a temple to Artemis in the city, the remains of which are still there, where the goddess was worshiped as Aptera, “Wingless Artemis.”

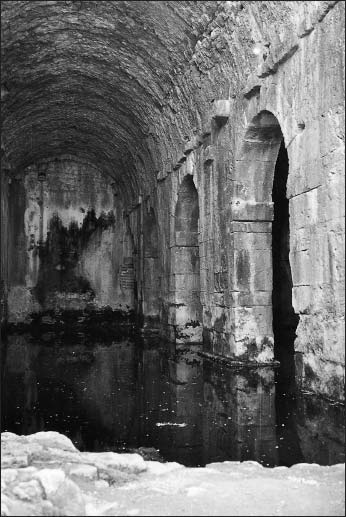

Aptera does not go back so very far as human societies are counted in Crete. When the Dorian Greeks with their iron weapons and warrior cult came down from the north and began to colonize the island, the Bronze Age civilization they replaced had already gone through two thousand years of achievement and decline. But these ruins have everything that can make a Cretan classical site fascinating to visit. Lying on an upland plain, well above sea level, it gives superb views of the high mountains to the south and the great sweep of Souda Bay, with Chania in the distance and the heights of the Akrotiri peninsula jutting out to the north. Recent excavations have revealed, among the tangles of ancient stone and spreading scrub, Doric columns lying where the cataclysm of the earthquake left them, the vestigial walls of a Roman street, the ruins of a Byzantine church, brick-vaulted underground cisterns, dark water still standing in one, and no sound but pigeons' wings.

One can wander at will here, sea on one side, mountain on the other. In spring and early summer the whole area is spread with wildflowersâhollyhock, rockroses, great clusters of dark blue vetchâand alive with the linnets and stonechats and pipits that are the present tenants. For lovers of old stones like us, the wilderness that is left after the fall of ancient citiesâwhich is not like any other kind of wildernessâthis place could hardly be better. In those addicted, the attention becomes in a curious way impartial, evenly distributed but without loss of sharpness: The eroded basins of a Roman bathhouse, and the extraordinary vividness of the poppies that blaze in the sun among them, have the same interest and the same age.

Aptera: a Roman cistern

We searched for traces of fresco painting on the patches of plaster still remaining on the ruinous walls of the Byzantine monastery dedicated to St. John the Theologian. There seemed to be an orangey or ochreous streak here and there, some configuration that might indicate human likeness, human intention. Inveterate, this habit of seeking our own image everywhere. But it is time and decay that have made these marks; they have beauty but no designâor none that we could recognize.

Rethymnon, capital of the province of the same name, is the next town of any size eastward on the road that runs practically the whole length of the island from Kissamou to Sitia, linking all the coastal areas. The principal cities and most of the beach resorts are situated on this north coast.

It's a good road, a lot of it of recent construction, well marked and well surfaced, easily the best road on the island. All the same, we drove warily along it. On Cretan roads the incongruous and unexpectedâelements generally presentârequire a high level of alertness. Someone might be dragging a handcart loaded with oranges, or crossing the road with buckets in a quest for water. Bypass roads are almost nonexistent, and you shift abruptly from the speed and freedom of the open road to a seaside street with shops and bars and parked cars and people in beach dress wandering about, then out again, just as abruptly, with ranks of mountains on one side and the glittering reaches of the Aegean on the other. Also slightly unnerving is the general use of the hard shoulder as a second lane. There should be two lanes, really, on either side, to cope with the volume of traffic, which increases dramatically in the summer. Perhaps the money was lacking for such a large-scale project; the cliffs come down sheer in many places, and there is not much space between them and the shore. However that may be, the hard shoulder, which is narrow when there is one at all, and sometimes strewn with broken stones or the debris of ancient picnics, and which we are conditioned to think of as for emergency use only, is generally regarded by Cretansâwho totally lack this conditioningâas an extra lane. Drivers wanting to overtake will sound their horns to make you get over, and they will quickly become angry if you fail to do so.

Cretan driving habits have a quality all their own, which must be seen to be appreciated. It is not self-righteous or unmannerly or neurotically impatient. There is a sort of proud carelessness about it, lordly and dangerous. The quality is best summed up by the Greek word

palikari,

which has no real equivalent in English. The palikari is the hero, the freedom fighter, the patriot. He goes back centuries to the days of Turkish occupation, when he took to the mountains and became an outlaw and fought a guerilla war against the oppressor in which no quarter was shown on either side. You see him in innumerable old pictures, with tasseled cap and fearsome mustachios, breech-loading musket by his side and curving, double-bladed yataghan at his belt.

Village education in Crete hasn't changed so very much since those days. The palikari is a hero still, and a model of behavior, to schoolboy and adult alike. I remember once sitting outside a café in a quiet square when an open sports car of antique design came very fast around the corner and pulled up with extreme suddenness, narrowly missing a war memorial and an ancient woman in black. Out of it stepped a young man who strode into the café without a backward glance. “There goes a palikari,” one of the men at a nearby table said, and there was a note of unmistakable admiration in his voice.

The last stretch of road, after it rejoins the coast at the base of the Drapanon peninsula, is spectacular, with the great expanse of the Almirou Bay on your left and the heights of Psiloritis rising before you. The cliffs descend in places very steeply, often to the verge of the road, and where the rock is split or heavily eroded, it shows a warm, reddish color that glows in the sun. On the outskirts of Rethymnon, as on the outskirts of all towns of any size in Crete, there are huge roadside posters advertising cigarettesâa rare sight these days, at least in Western Europe.

Rethymnon is guarded by a Venetian fortress massive in its proportionsâit is generally considered the largest the Venetians built anywhere, a response to the increasing frequency of Saracen pirate raids, one by Khair ed-Din Barbarossa in 1538, another by Dragut Rais in 1540, and two by Uluch Aliâan Italian renegade of notable savageryâin 1567 and 1571. The last of these was very destructive; large areas of the town were burned to the ground.

The Venetians succeeded to a large extent in suppressing piracy, but despite the fort's vast size and formidable defenses, Rethymnon fell to the Turks in 1646 after the briefest of sieges. The invaders did not obligingly expose their ships to the Venetian cannon, but attacked from the west and south, bombarding the garrison into submission. Seeing these towering battlements, so costly in men and money and materials, and in the end so unavailing, I was reminded of another empire and another wall, one built by forced labor on the orders of the Roman emperor Hadrian, running from coast to coast across the north of England, constructed to keep out the Picts. The Roman legionaries, used to a warmer climate, must have shivered in those bitter winds, looking always north toward the lands of the accustomed enemy. But the real threat, which no one had envisaged, and against which the wall was useless, came from the south, from the Saxon tribes that would come by seaâ¦.

Here in Rethymnon, in the vast open space enclosed by the fortress walls, among the remains of the Venetian barracks and storehouses and cisterns and powder magazines, grow flamboyant red and yellow poppies, and wild oats bleached by the sun, and clumps of white marguerites. Cretan dittany

(Dictamnus creticus)

grows in cracks in the walls. A medicinal infusion of very ancient fame is made from this herb, mentioned by Pliny and Aristotle and Theophrastus, who wrote the first systematic treatise on botany. A plant so celebrated for its healing properties naturally accumulates stories around it. In

The Aeneid

Virgil relates how the hero Aeneas, when suffering from an arrow wound, was healed by means of this wonderful herb, which his mother Aphrodite brought him from Crete. In antiquity, when the Cretan wild goat, or

kri-kri,

was common all over the island, it was believed that they could cure themselves of the arrow wounds inflicted by hunters with a poultice they knew how to make from this plant. This phenomenal sagacity, however, did not prevent the kri-kri from being hunted almost to extinction; today it is found in a wild state only in the gorge of Samaria and the surrounding country.

There is a mosque in the enclosure of the fortress walls, dating from the days of Turkish rule. It was a church before this and a church again after, as Christian and Muslim took their turns in dominating the island. It was the Turks who added the dome, which is beautifully proportioned, and the delicately carved

mihrab

or prayer niche, set in the

qiblah,

the wall that indicates to the faithful the direction of Mecca, to which they turn when they pray. And it was the Turks who organized the interior space into that of a square, a simple enclosure of four walls, in vestigial memory of Mohammed's private house in Medina, where the earliest followers of Islam gathered to pray.

The dome and parts of the windows have been restored in recent years, but this timeâfinallyânot to mark conquest or demonstrate religious supremacy, but because the building is beautiful and can be put to good use. On this particular day we found a busy scene going on inside, with people on ladders, and pieces of plywood cut into various shapes, and all manner of boxes and bundles lying around. A group of artists from Athens were preparing an exhibition of their work. One of them paused to explain it to us. I was relieved that she was able to do this in English. My Greek was once reasonably fluent, good enough at least to argue with taxi drivers or hold my own in discussions about the cost of living and the shortcomings of the Athens governmentâtwo principal topics of conversation then and now. But that was half a lifetime ago.

The group was called Touch. They made sculptures, ceramics, mobiles. They had been invited to use this building, which gave them more space than they usually had and so allowed them to show larger and more ambitious works. The woman who was telling me this was clearly exhilarated at the prospect. She was worried about the wind from the seaâthey would have to keep the doors closed on that side. But it was a marvelous place for an exhibition. She gestured: the circular space, the clear sea light that came through the windows spaced at intervals all around, the noble proportions of the dome. Very cheering, this enthusiasm, and moving too: Elements that for centuries made this a place of worship for mutually exclusive and hostile faiths now eminently qualify it for devotion of another kind, nondenominational, multiracial, all-inclusive.