Read The Rise and Fall of Modern Medicine Online

Authors: James Le Fanu

The Rise and Fall of Modern Medicine (9 page)

The tragedy of Orwell's life is that when at last he achieved fame and success he was a dying man and knew it. He had fame and was too ill to leave his room, money and nothing to spend it on, love in which he could not participate; he tasted the bitterness of dying. But in his years of hardship he

was sustained by a genial stoicism, by his excitement about what was going to happen next and by his affection for other people.

26

Orwell's fate has profound symbolic significance. Like the experience of the Oxford policeman Albert Alexander, who was the first person to receive penicillin, Orwell's brush with streptomycin is a reminder to future generations of the difference that anti-tuberculosis drugs would make to so many people's lives. Orwell died on the cusp of the paradigm shift. Another couple of years and he would have been spared the bitterness of a premature death to live on for several more decades. Who knows what else he might have achieved?

In the aftermath of the brilliant and lucid manner in which tuberculosis had been shown to be a treatable disease, the Randomised Controlled Trial (shortened to RCT) blossomed, just as Bradford Hill had hoped, to become the standard way of evaluating new drugs. As his protégé Richard Doll observed in 1982: âFew innovations have made such an impact on medicine as the controlled clinical trial designed by Sir Austin Bradford Hill . . . thirty-five years later the structure, conditions of conduct and analysis of the currently standard trials are, for the most part, the same. Its durability is a monument to Sir Austin's scientific perception, common sense and concern for the welfare of the individual.'

27

A minority were unconvinced. In a letter to the

British Medical Journal

in 1951, âa blast of the trumpet against the monstrous regiment of mathematics', a physician from Sunderland, Dr Grant Waugh, comments on

the outbreak in epidemic form of a disease of pseudo scientific meticulosis. The symptoms of the condition are characterised by: a) evidence of a certain degree of cerebral exaltation; b)

an inherent contempt for those who cannot understand logarithms; and c) the replacement of humanistic and clinical values by mathematical formulae. The systemic effects of this disease are apparent; patients are degraded from human beings to pricks in a column, dots in a field, or tadpoles in a pool; with the eventual elimination of the responsibility of the doctor to get the individual back to health.

28

Behind the bombast Dr Waugh was making a serious point, for, as will be seen, clinical trials were not infallible and when improperly conducted could give rise to false conclusions that could not be rectified by any amount of objectivity conferred by ârandomisation'. The RCT, however, was to prove utterly indispensable in the evaluation of the explosion of new drugs that occurred in the 1950s and 1960s. The thalidomide tragedy in 1960 forced governments around the world to insist that all new drugs be formally tested for their effectiveness and safety in randomised controlled trials as a requirement for the granting of a product licence. Thus Bradford Hill established the gold standard by which the merits of modern drug therapy must be measured.

29

Bradford Hill's second indestructible achievement in his

annus mirabilis

of 1950 was to show that smoking causes lung cancer. Nowadays this seems so obvious as to be unremarkable, but back in 1950 it was not, for the simple reason that as a direct consequence of two world wars in thirty years virtually everyone smoked. Tobacco had proved as much of a solace in the trenches at Passchendaele as during the London Blitz and, when not calming the nerves, âa smoke' was at least something to

accompany the endless cups of tea that filled the long, empty hours so characteristic of total war, when citizens were unable to pursue their legitimate occupations. It is easy to appreciate how difficult it could be to show that smoking caused lung cancer if everyone smoked, because both those with and those without the disease would be smokers. Indeed, only statistical methods could resolve this question, because statistics can see âbelow the surface' of things to identify relationships that would otherwise remain obscure.

It has been noted that lung cancer replaced tuberculosis in a metaphorical sense as part of the paradigm shift from one pattern of disease to another, but lung cancer also replaced tuberculosis in a literal sense in 1950, as for the first time the number of deaths from the disease â 13,000 â exceeded those from tuberculosis.

30

And while the toll of tuberculosis rapidly receded over the next few years under the onslaught of anti-tuberculosis drugs, that of lung cancer soared. There are further interesting comparisons. The tragedy of both diseases was that their victims died young or, in the case of lung cancer, relatively young, in their fifties and sixties. And, just as tuberculosis prior to 1950 was essentially an incurable disease, so was lung cancer. Indeed lung cancer was the more grievous of the two illnesses as, with the very infrequent exception of those in whom the disease was detected early enough to be surgically removed, most patients died within eighteen months.

31

From this perspective it is almost impossible to overstate the importance of Bradford Hill's implication of smoking, as this dreadful, untreatable, escalating disease suddenly became âpreventable' through the simple expedient of people not smoking. And it is almost impossible to overstate just how significant this was for the subsequent development of medicine, as over the next fifty years this example of the âpreventability' of lung cancer was

enormously influential in promoting the notion that most cancers and other common causes of death might also be preventable by similar âlifestyle' changes (as will be explored in detail in the final section of this book).

Bradford Hill's logical inference from statistical data â his demonstration of smoking's causative role in lung cancer â was a masterpiece. The simplest of all medical statistics are, as already noted, the âvital statistics' recording the unarguable event of death. When analysed over a defined period, they may display a characteristic pattern such as the rise and fall typical of an infectious epidemic. The collection and interpretation of such vital statistics constitute a form of scientific observation little different in its way from âobserving' the effects of disease in an individual. But statistics in this form can only report what has happened; they cannot produce any insights into why it has happened. For this it is necessary to move from simple observation to performing an âexperiment', which, like the Randomised Controlled Trial, is fairly straightforward and again essentially involves making a comparison. When the various aspects of the lives of a group of people with a particular disease are compared to those of another group without the disease, differences might emerge which, it might be inferred, could theoretically be the cause of the disease being studied.

In 1947 Bradford Hill, along with Edward Kennaway of St Bartholomew's Hospital and Percy Stock, the government's chief medical statistician, were asked by the Medical Research Council to investigate whether smoking might explain the âstartling phenomenon' of the fifteen-fold increase in the death rate from lung cancer in Britain over the previous twenty-five years. They were subsequently joined by Dr Richard Doll, who later recalled the division of opinion that reflected the prevailing views of the time:

Kennaway was particularly interested in the possibility of smoking being a factor, but I don't think anybody else was. Bradford Hill certainly wasn't particularly keen on smoking as a cause, nor was I, while Stock was particularly keen on the effect of general urban atmospheric pollution. I must admit I thought the latter was likely to be the principal cause, though not pollution from coal smoke which was terrible in those days but which had been prevalent for many decades and hadn't really increased. Motor cars, however, were a new factor. If I had to put money on anything at the time I should put it on motor exhausts or possibly on the tarring of roads. But cigarette smoking was such a normal thing and had been for such a long time that it was difficult to think it could be associated with any disease.

32

The main problem facing Bradford Hill was that 90 per cent of the adult male population were smokers, so clearly it would not be possible to implicate tobacco simply on the grounds of whether someone smoked or not. Rather, it was necessary to identify some biological phenomenon from which it would be reasonable to implicate tobacco. The most obvious is the âdose-response relationship' â the higher the âdose' of tobacco the greater the âresponse', or incidence, of lung cancer. The statistical method was known as the âcase-control' study, where âevery case' of lung cancer was compared with a âcontrol' who was similar in every way other than suffering from some other disease. Theoretically, then, if the heavy smokers were disproportionately represented among the lung cancer group compared to the controls, one might infer that smoking was the cause of the disease. Though this seems straightforward in principle, in practice it is quite difficult, mainly because it is so difficult to ensure that the âcases' and âcontrols' are truly

comparable. The investigation, therefore, had to do much more than record how much a person smoked; rather,

a range of potentially relevant factors had to be taken into account: the age, sex, urban or rural residence, and social class of the subject; occupational history; exposure to air pollutants; forms of domestic heating; and the history of smoking including for those who had smoked, the age of starting and stopping, the amount smoked before the onset of illness, the main changes in smoking history, the maximum amount smoked, the practice in regard to inhaling and the use of cigarettes or pipe.

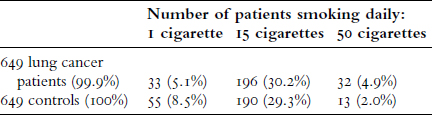

Starting in April 1948, doctors in twenty hospitals in London notified Doll of any patients suspected of having lung cancer. Doll would then arrange for a âlady almoner', as social workers were quaintly called in those days, to interview both the patient and two âcontrols', one with cancer of the stomach or colon and one from another of the general medical and surgical wards with a disease other than cancer. He found that 99.7 per cent of the lung cancer patients confessed to smoking, compared to 95.8 per cent of those with âdiseases other than cancer'. Such an observation by itself obviously proves nothing at all, but when the patients were subdivided into four groups depending on how much they smoked, ranging from âone cigarette' to âfifty cigarettes' a day, then it is possible to discern a trend of a higher risk of lung cancer among the heavy smokers (see page 64). Examining the final set of figures in the table, 4.9 per cent of lung cancer patients smoked fifty cigarettes a day, twice as high a percentage as the 2 per cent of controls â a subtle difference perhaps, but whichever way the smoking habit was investigated, either looking at the amount smoked every day, or the

maximum amount smoked, or the total amount smoked over the years, and so on, the same pattern emerged: the greater the amount of tobacco consumed, the higher the risk. For Doll and Bradford Hill the conclusion seemed inescapable: âIt is not reasonable, in our view, to attribute the results to any special selection of cases or to bias in recording. In other words, it must be concluded that there is a real association between carcinoma of the lung and smoking.'

33

Smoking habits between patients with lung cancer and controls

.

.

(From R. Doll and A. Bradford Hill, âSmoking and Carcinoma of the Lung',

BMJ

, 30 September 1950, pp. 739â48.)

We now know this only too well, but at the time things appeared very differently. Social habits had been incriminated in lethal diseases before, most notably drinking alcohol as a cause of liver cirrhosis, but this is a fate restricted to a minority of alcoholics. Smoking was different, as virtually everybody âindulged'. It was an intrinsic part of each and every social occasion and the offering of a cigarette an integral part of social (and often sexual) intercourse. Its incrimination in a lethal disease was thus a matter of the utmost gravity. The director of the Medical Research Council, Sir Harold Himsworth, strongly advised Bradford Hill and Doll that they should delay making their results public, as Doll subsequently recalled: âHimsworth said the

finding was so important he did not think we should publish it until we had found it again' (i.e., repeated the study and found the same results). They duly set to work, this time investigating lung cancer outside London (lest their findings might have been a fluke attributable to some unidentifiable âLondon factor'), but this proved unnecessary when a few months later an American study came to exactly the same conclusions.

34